INTRODUCTION

After the end of World War Two in 1945, the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) waged a 12-year anti-colonial war against British Malaya and Commonwealth forces in the jungles of the Federation of Malaya. The first incident occurred at Elphil Estate in Sungai Siput, Perak, on 16 June 1948 where three European plantation managers were killed. On 18 June 1948, the British brought emergency measures into law, first in Perak and then country-wide in July 1948.

Known as the Malayan Emergency, it was fought from 1948 to 1960 where military campaigns were embarked against the Communist Terrorists (CTs). Military forces were widely spread out in many parts of the Federation.

In 1950, Lieutenant General Sir Harold Briggs was the Director of Operations in Malaya. His strategies to combat the CTs were, first, to protect the villages on the outskirts of town and second, to isolate them from the CTs. He initiated the formation of Home Guard in Malaya as part of the “Briggs Plan”. This increases the local security among the population while building the confidence and morale of the people. At the same time it also encouraged the participation of the general population in the struggle against the CTs.

The introduction of Home Guard also released the military and police for anti-terrorist operations and separated the CTs from their main sources of supply and recruitment. The Federation have other defensive forces before the formation of Home Guard such as Special Constabulary (SC), Police Jungle Squad, Police Field Force (PFF) and Auxiliary Police (AP).

It was a challenging task forming the Home Guard in 1951. The withdrawal of Japan at the end of World War Two left the Malayan economy disrupted where problems faced include unemployment, low wages, and high levels of food inflation above the healthy rate of 2-3%. Economics was not good in those days and many were not able to find work. This also affected their livelihood and health; hence great efforts were needed to ‘win’ over the people to the government side especially in new villages and Chinese resettlements.

|

HOME GUARD

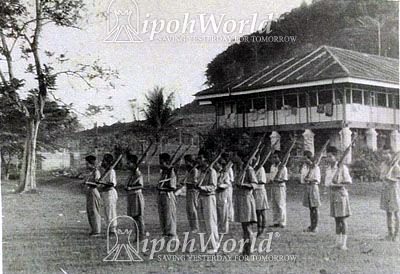

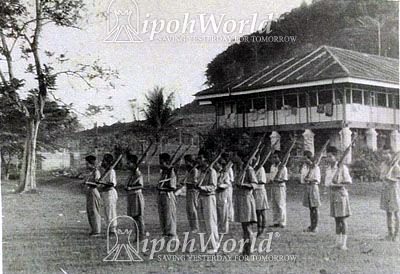

The first home guard unit that was formed during the Malayan Emergency was by Hembry's Own Bloody Army (HOBA) after members of the CPM shot and killed the three European planters at the Elphil Estate, Sungai Siput.

Hembry formed a local Home Guard unit with the help of his Platoon Sergeant Eusoff from the Perak Malay States Volunteer Force who recruited and taught them basic arms drill and fire discipline to guard not only the Kamuning Estate bungalows but also the estate factory and office that were at risk of attack by the CPM.

|

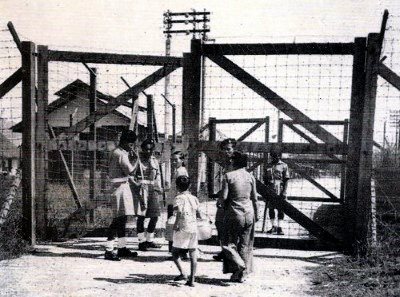

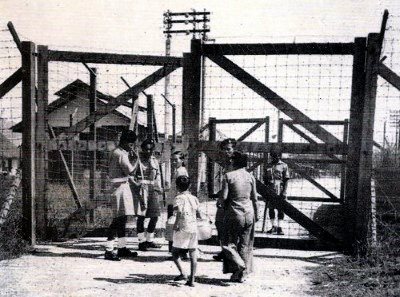

| HOBA Home Guard Unit, 1948. Source: http://www.ipohworld.org |

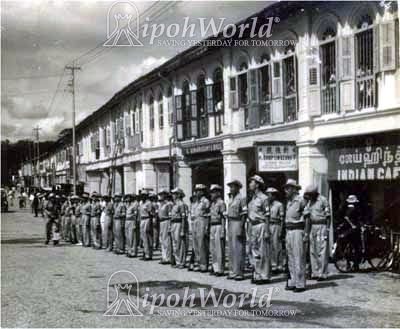

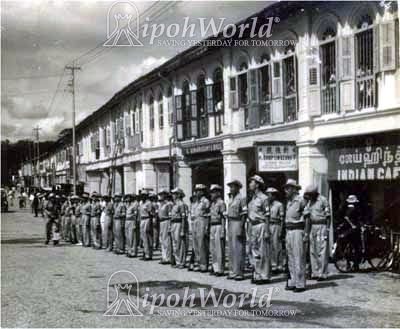

In 1951, a Home Guard force was legislated to be organised in all states in Malaya, giving them responsibilities to look after strategic assets location such as weapon depot, tin mines and rubber estates. They also assist the Police in manning road blocks and carrying out identity inspection. A civil force comprising of all races embodied under the Emergency (Home Guard) Regulations 1951, Home Guard units were formed in new villages, Chinese resettlements and kampongs and they come under the command and control of the respective State Home Guard Officer except the states of Kedah and Perlis merging as one. An office for the Inspector General Home Guard, overseeing the overall administration of the entire force, was located in the Federal capital.

Enrolment is compulsory for all able-bodied male between the ages of 18 and 55 which includes Malays, Chinese, Indians, Eurasians and Orang Asli.

Home Guards were part-time soldiers, given only basic training and were required to perform a limited role when they are called to duty. Primary role of the Home Guard were maintaining a check on food and controlled articles, surveillance of strangers in their locations, and defence of the barbed wire fencing. A Home Guard performed duty once every week or 10 days, with no payment of salary or allowances. Part of a defence strategy, their role was ‘static local defence’ and ‘manning of checkpoints’ to cut off supplies to CTs, particularly in the areas of new villages and Chinese resettlements.

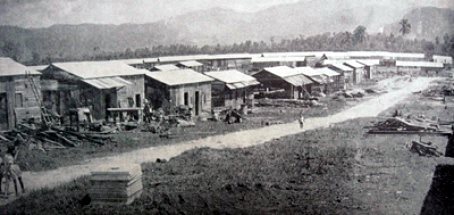

It was not an easy task forming Home Guard units in the beginning, particularly getting the residents in new villages and Chinese resettlements to cooperate where the people came under threats of the CTs. Curfew and food rationing had brought inconveniences that the majority did not like. The poor Malaya economy compounded the hardship as many were without work. Unlike those living in kampongs, Chinese did not readily take to becoming Home Guards. It took some efforts before signs of positive changes were seen and gradually Home Guard units were formed according to plan with the support of the village leaders.

|

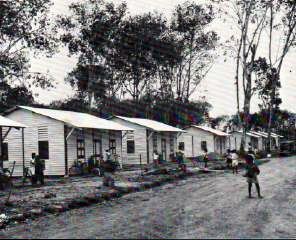

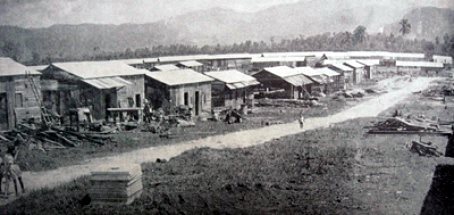

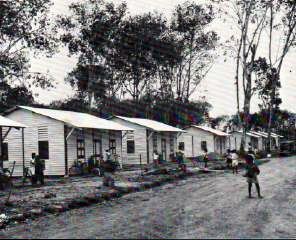

| Jinjang New Village in the 1950s. Source: https://aliran |

|

| Home Guard unit in Ulu Langat, Selangor.

(Malaysian National Archive)

|

In Perak, countless incidents of terrorists firing at Home Guard posts were reported in the early days. These were attempts to put fear and discourage the villagers from performing Home Guard duty. One major incident occurred in 1956 was, the terrorists raided a post in Simpang Pulai New Village in wee hours of a Saturday morning. Under the threat of lives, the terrorists took away 10 shotguns from the Home Guards. Following this incident, a major reorganisation was put in place with changes made to operating procedures and training of Home Guard members. It was a difficult time but the Home Guards took it well. It also brought an outpouring concern on the part of the villagers and many came forward voluntarily to register their names. This was the beginning of an ‘unbelievable’ change that was subsequently found in new villagers and Chinese re-settlements.

|

| Home Guards in Tapah wearing their “HG” armbands, 1952. Source: http://www.ipohworld.org |

|

| Workers on rubber plantations taken to work under the protection of Special Constables in 1950. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki |

Role

Primary role of the Home Guard:-

| a. |

To have the citizens in new villages, Chinese resettlements and kampongs take equal responsibilities in protecting their home with a unit of Home Guard made up of multi-racial citizens. |

| b. |

To eliminate the threat of CTs in areas not covered by military forces and police such as tin mines and rubber estates besides assisting them to patrol and occupy those areas. |

| c. |

To stop the spread of Communist ideologies and Min Yuen activities into new villages, Chinese resettlements and kampongs. |

|

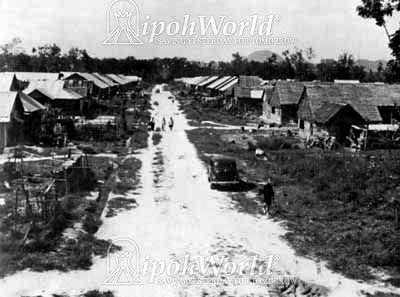

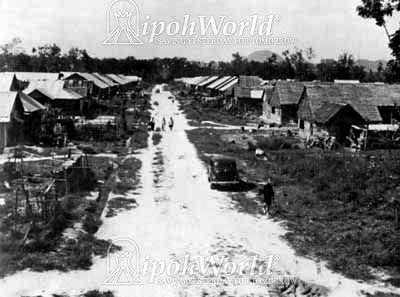

| Kampong Simee New Village in Ipoh, 1951. Source: http://www.ipohworld.org |

|

| Briggs Plan: A New Village in the 1950s. Source: https://twitter.com/ |

|

| General Sir Gerald Templer speaking to villagers in Kampong Merbau New Village, Ayer Tawar, 1954. |

|

| Home Guards manning a post in Tanjung Malim.(Malaysian National Archive |

|

| Home Guards checking vehicles at a road block.(Malaysian National Archive) |

|

| Home Guards performing their duty. Source. http://konflikdanmiliter. blogspot.com. |

Command and Control

In April 1951, Lieutenant General Sir Harold Briggs formed the Federal War Council (FWC) and Home Guard units were formed in all states in the peninsular. They came under command and control of the State Home Guard Officer of the state. This post was initially filled by a seconded senior British Army officer. Kedah and Perlis states were merged as one.

Each state had an establishment of full time personnel called Permanent Staff (Assistant State Home Guard Officer, District Home Guard Officer, Home Guard Inspector, Home Guard Instructor) to manage and conduct training of Home Guard personnel at designated district level.

|

| State Home Guard Officers, 1958. (Malaysian National Archive).

|

Personnel Strength

At the height of Malayan Emergency, the force had a strength of 250,000 personnel spread out from Johor to Perlis including the East Coast. Each state had an establishment of Permanent Staff to manage and conduct training at designated places. There were 30,000 registered members in 1951 comprising 25,400 Malays, 3,500 Chinese, 800 Indians and 300 other races. The Home Guard force was subsequently placed under the charge of military and an additional 42,000 citizens were trained. The numbers increased to 77,000 by July 1951 and it reached 99,000 by end of the year.

To further encourage the participation of Chinese citizens, Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), then under the leadership of Sir Tan Cheng Lock, were brought in to give assistance. In mid 1953, the Chinese participation have reached 79,587 out of the 244,645 Home Guards. 129 out of the 323 new villages and Chinese re-settlements have their own Home Guard units in September 1954.

Some 152,000 Home Guards had become fully responsible for local defence in 173 new villages and Chinese resettlements at end of 1955.

|

Kinta Valley Home Guard

Kinta Valley Home Guard (KVHG) was established by the Perak Chinese Tin Mining Association with the support of General Sir Gerald Templer, High Commissioner in Malaya, soon after he arrived in February 1952. Unlike State Home Guard, KVHG was formed and financed jointly by the Perak State Government and the owners of tin mines. It was an all-Chinese Home Guard unit.

Perak State recruited and trained some 4,000 members. Many of General Templer detractors thought it would be a disaster to supply arms to what was to be a large Chinese Home Guard unit for the defence of Chinese tin mines. Some leaders recalled what had happened to the weapons supplied by the British to the Malayan Peoples Anti-Japanese Army in World War Two, many of which were secretly hoarded at the end of the war and used later against the British in the Malayan Emergency.

Nevertheless, General Templer gave his support to the KVHG and work with the assistance of Colonel H. S. Lee, Leong Yew Koh, and Dato’ Lau Pak Kuan then President of the Perak Chinese Tin Mining Association who played an important role in its funding, organization, and deployment. KVHG was often described as a “Chinese private army” because of its close connections with the Koumingtang as Colonel Lee H. S. had been a Colonel and Leong Yew Koh, a Major General in the Koumingtang Army during World War Two. When General Templer left Malaya in 1954, it was reported that there were 323 tin mines defended by the KVHG which remained operational until the end of the Malayan Emergency in June 1960.

KVHG successfully defended 323 tin mines and was operational from 1953 to 1960.

|

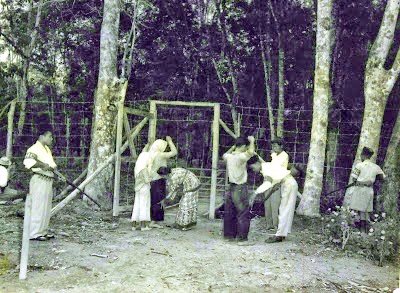

| Training of KVHGs in Ipoh, Perak.

(Malaysian National Archive). |

|

| General Sir Gerald Templer and his assistant Major Lord Wynford (on his left) visiting KVHGs. On the right is Wong Fook Seng, commander of the unit. Source: pinterest.com/aimanalhakim/ |

|

| KVHG Foo Weng Fun with a colleague at No. 7 Base in Batu Gajah, Perak, 1958. Source: http://www.ipohworld.org/ |

Chinese Participation

A large number of Chinese in Malaya have taken an active role and contributed their service in preserving order and security during the Malayan Emergency. They have displayed loyalty to the King and Country in doing service as Home Guards. Home Guard personnel were not paid salary or allowances for the duties they performed, unlike uniformed members of the former State Volunteer Forces, the Territorial Army, and the People's Volunteer Corps (RELA) today who receive payment for the performance of duty and attendance at training.

As the state of security had improved by 1958, more States were declared “White”. The Home Guard force was officially disbanded on 30 June 1959. Chinese participation had reached 79,587 in 1953 where 129 out of 323 new villages were manned by Chinese Home Guards.

NATIONAL SERVICE

It is of interest to recall that in 1951 a Chinese boy joined the armed services from the age of 17 years 7 months and remained in service with the Armed Forces until his retirement aged 50. During the Malayan Emergency, the Government enacted a law to conscript youths for National Service. Male youths of the age of 18 years and above were picked at random.

This is a brief recollection of an old soldier who has had the privilege to be able to serve the nation for over 32 years.

Major Tan Hock Hin (Retired), also known as Tommy, was conscripted for National Service in April 1951 and was called to report for training at the Police Training Depot, Kuala Lumpur. As he was not keen to become a policeman, a friend got him interested to join the Ferret Force (a British establishment) where he reported for training at Segenting Camp, Port Dickson, on 1st May 1951. The Camp Commandant had some hesitation in accepting him initially because he was under the age of 18. Tommy asked to be allowed to undergo the training and that the Commandant can decide after training whether he can be accepted. Tommy completed the six weeks training and passed. By then, Ferret Force had been renamed Civil Liaison Corps.

Tommy was appointed a Junior Civil Liaison Officer (JCLO). JCLOs were deployed with Commonwealth troops found scattered throughout the peninsula. They go into jungles and operational areas and performed the role of interrogators and interpreters. JCLOs also assist in gathering intelligence in the local community where they are stationed.

Tommy was posted to IV Queen’s Own Hussars (British Armoured Corps) which had its base in Raub, Pahang. Its primary tasks were to keep the roads safe and lay in ambush where terrorists might be found. Areas of their operation stretches from Jerantut to Tranum, to Bentong, and the winding Gap road to Kuala Kubu Baru. Gap road was considered particularly dangerous as its hilly grounds gave the terrorists an advantage. Contacts between security forces and terrorists were reported almost daily. After six months, XII Royal Lancers replaced IV Queen’s Own Hussars when the latter completed its tour of duty in Malaya and Tommy was re-assigned to this unit.

|

|

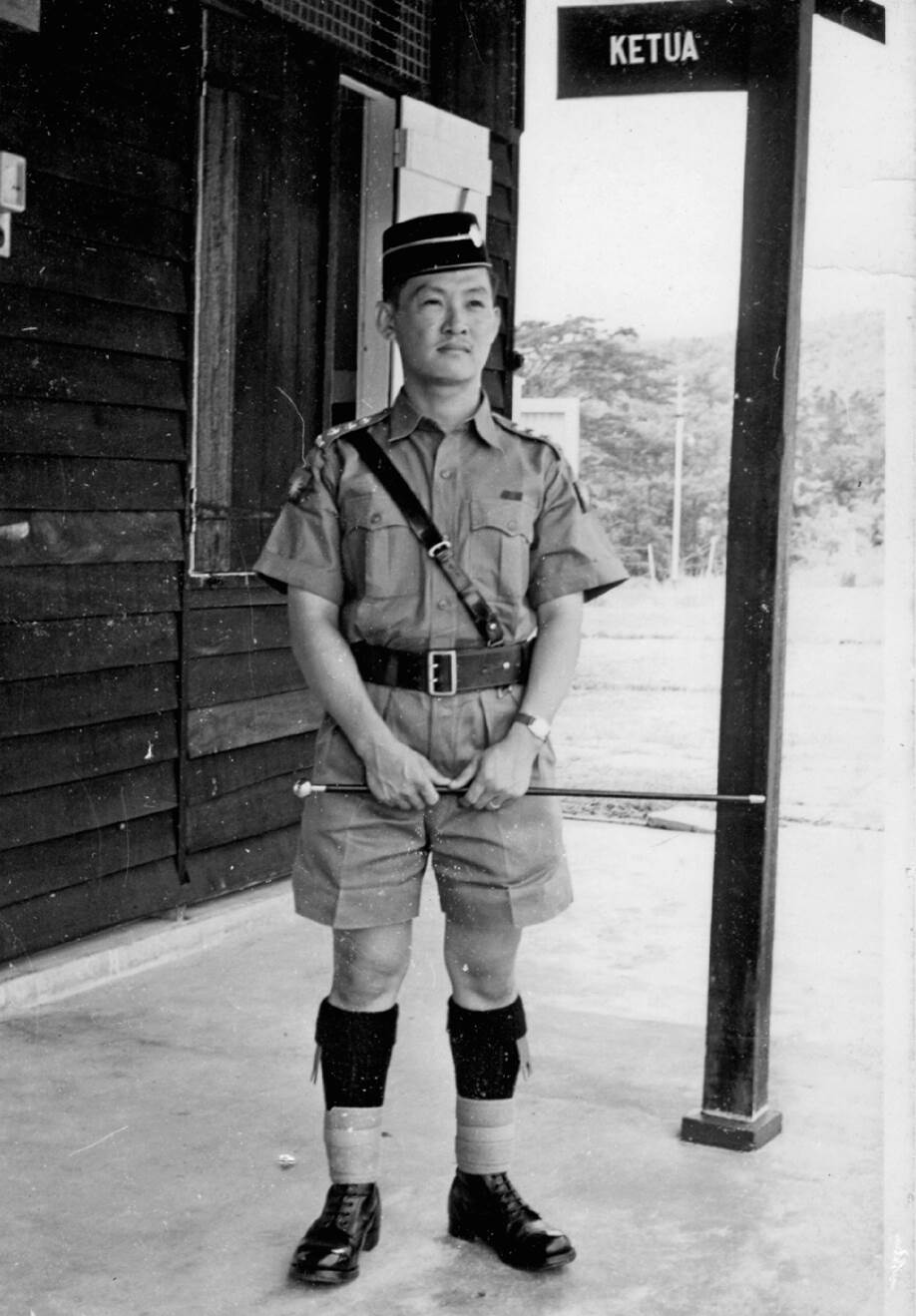

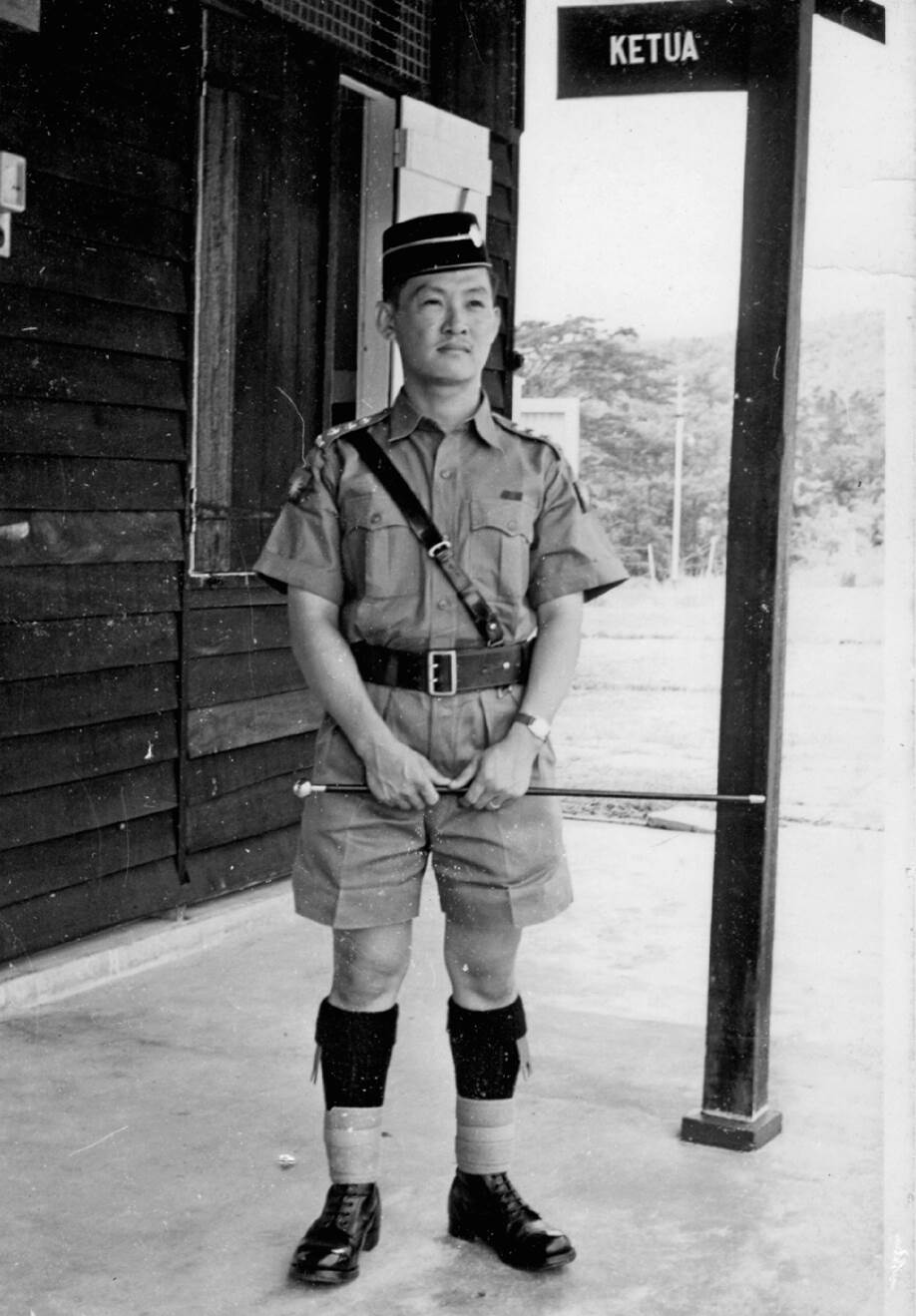

| JCLO Tan Hock Hin attached to IV Queen’s Own Hussars in Raub, Pahang, 1951. |

Raub was known as the CPM’s national operational base in 1951-1952. Raub district was classified as one of the terrorists’ most active areas, particularly places around the Tras region and the winding Gap road to Kuala Kubu Bahru.

Enemy Attacks

On 6 October 1951, British High Commissioner in Malaya, Sir Henry Gurney was killed by terrorists in an ambush at a sharp bend near the 57th milestone while traveling with his wife to the highland resort of Fraser’s Hill. Terrorists had laid in ambush at a sharp bend where drivers were forced to drive slowly. Sir Henry was accompanied by police escort in two vehicles; a land rover moving ahead of his Rolls Royce and a scout car in the rear. Just as the first two vehicles came into the ambush zone, the terrorists opened fire. All but one of the policemen in the first vehicle were killed or wounded. The driver of the Rolls Royce was badly wounded and the limousine rolled to a halt, riddled with bullet holes. His wife was unhurt. It was concluded later that Sir Henry left his car to draw away the terrorists’ fire thereby saving the life of his wife.

Few days before the incident where Sir Henry was killed, a vehicle of IV Queen’s Hussars was fired upon while on patrol, barely 100 yards from the same spot. Tommy was inside that vehicle. Police and the military took turns patrolling the Gap road.

|

| JCLO Tan Hock Hin with IV Queen’s Own Hussars on road patrol along Gap road to Kuala Kubu Baru, 1951. |

|

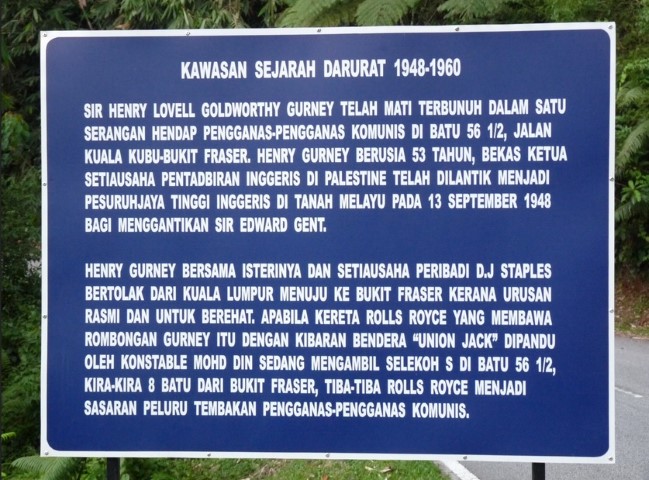

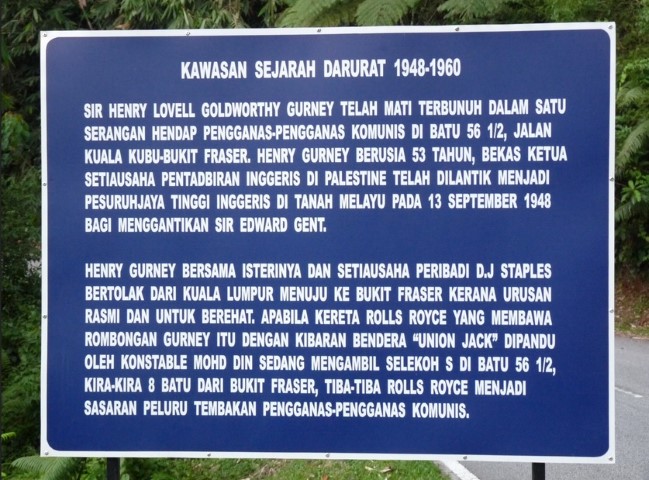

| Signboard showing the ambush location, Gap road to Kuala Kubu Bahru. |

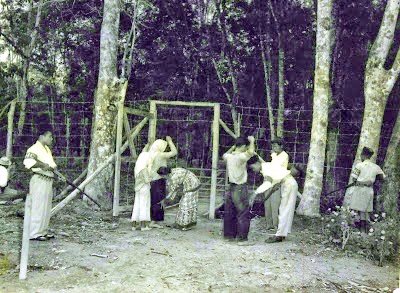

Following the assassination of Sir Henry Gurney, the Government took unprecedented measures to deal with the situation. The measures taken include imposing dusk to dawn curfew in selected places and bringing the people living freely in rural areas into designated places, fenced by barbed wire and guarded by Special Constabulary, a branch of the Malayan Police. The Briggs Plan was credited as one of the significant steps that led to the eventual defeat of militant communism in the country.

In 1952, General Sir Gerald Temple was appointed as the new British High Commissioner. A career military officer with a distinguished record of service, he inherited the Briggs Pan and oversaw its successful implementation. He got down to work quickly and brought about laws to enforce the numerous measures to counter the communist insurgency. Food control measures and rationing were imposed in rural areas and Home Guard to be formed nationwide. The establishing of new villages and Chinese resettlements and formation of a Home Guard force were two major features in the Briggs Plan.

At the end of one year, Tommy accepted the post of Home Guard Inspector offered to him. He had the choice of remaining as JCLO or take up the new post. He served as Home Guard Inspector in the Perak State Home Guard from 1 May 1952 to 30 June 1959.

New Villages

The purpose of the Briggs Plan was to undermine the Communist Min Yuen group (non-uniformed members that assisted the uniformed terrorists) and cut them off from the rural settlers who were the source of supply of food, money, information and bringing new recruits to the Communist cause.

The Briggs Plan was deemed as the largest and most important social engineering project in South East Asia after the war. It regrouped and transferred about half a million Chinese rural dwellers into over 400 new villages and resettlements, each with a household of approximately 100 families or more. In Kinta, an estimated 106,889 people were relocated into 34 new villages from 1949 to 1952. The primary aim in bringing people to live inside barbed-wire fencing was to prevent the terrorists from getting to the villagers. A section of the locals were found hostile while some others were suspected of harbouring influences against the interests of the majority. Economics then was not good and many were unable to find work after they moved into new villages. One notable experience was those that came from Lenggong, Upper Perak, to Dindings district. Majority of them were Kwongsai and they preferred cultivating tobacco for a livelihood. Land around the Ayer Tawar area were found unsuitable for growing tobacco, yet these people refused to switch to rubber tapping or work related to rubber trade which was the main industry here. It took great efforts on the part of government agencies to ‘win’ over the cooperation of the villagers.

In the new villages and resettlement areas, all the houses were arranged in straight rows in a compact and regular layout and all cooking was communal with portions of food being handed out to each individual. Any food removed from the village required a police permit to be obtained. The villages were surrounded by perimeter fences of double-barbed wire some ten feet high and 30-45 feet apart, to prevent villagers from throwing food over the fences to the Communists. The occupants were also monitored by means of police units and members of the Home Guard with watch towers and mercury vapour lamps overseeing the brightly lit areas at night. Curfew orders issued by local police stations instructed members of the public to remain indoors between the hours of 6 pm and 6 am.

|

| Sungai Nipah New Village, Negri Sembilan. Source: Ray Nyce (1973) |

The CTs were deprived of the food and medical supplies that they had previously obtained from the isolated smallholders and plantation workers. This level of control of the Chinese rural population remained until the authorities believed that the area was clear of the Communist threat.

The setting up of new villages and Chinese resettlements and food rationing soon began to jeopardize activities of the CTs. Its pursuit on overall control and coordination between the military and civil administration ultimately worked to enhance the impact. Supply lines of the Min Yuen group bringing supplies through the village main gates began to disrupt and this gradually brought a change to the villagers’ attitude and outlook.

|  |

TERRITORIAL ARMY

The Government decided to retain the spirit of volunteerism after disbandment of the Home Guard with the formation of a new volunteer force called Territorial Army (TA) or Tentera Tempatan under the legislation of the Territorial Army Ordinance, 1958. The purpose of having this force was to make available a pool of manpower reserve to augment the regular force in times of emergency.

Malaya had this volunteer force in the pre-war days, in Penang, Perak, Kuala Lumpur, and Malacca, and they were called the Straits Settlement of Penang Volunteer Force, Straits Settlement Volunteer Transport Company, etc. These units had taken active roles in the defence of Malaya in World War Two. Some of the members were imprisoned as prisoners-of-war during the Japanese Occupation.

TA was established on 1 July 1958 with its command and administrative headquarters located in the Ministry of Defence (Mindef). Tommy’s name was found in the first list of candidates selected for transfer to the TA. He was posted to a unit to be formed in Seremban named Pasukan Pertama Tentera Tempatan Negeri Sembilan (1 TTNS) on 1 July 1959. Depending on the size of the State, many States have more than one Tentera Tempatan unit.

Both men and women falling within the approved age readily volunteered. The pleasant surprise was people from all races came forward. Depending on the corps they joined, volunteers were required to attend 120 hours training annually, or 240 hours for those in supporting arms, and two weeks annual camp every year. Volunteers received payment of fixed allowances for attendance at training and salary according to their ranks at annual camps.

A major reorganisation of the TA came into place on the outbreak of Indonesian Confrontation. A new name was adopted, called Askar Wataniah with Colonel Yeop Mahidin appointed as its first Director. Known as the father of Wataniah, Col Yeop Mahidin had previously led a local Malay resistance group and carried out guerrilla warfare known as Wataniah Movement against the Japanese in Pahang. The entire reserve force was restructured to meet the needs of the time. Several new units patterned after infantry battalion structure were formed, and a new section called Local Defence Corps (LDC) or Pasukan Pertahanan Tempatan was established. This brought a two-fold increase in numbers to our reserve army.

|

| Permanent Staff 1 TTNS, 1959. |

The state of security took a serious turn in the face of Indonesian Confrontation in 1965. Both Regular and Territorial forces worked tirelessly in producing plans to face the challenges ahead. TA personnel were mobilised to guard selected “key points”. TA infantry battalions were mobilised to provide security to a new highway under construction in Perak/Kelantan. Nucleus of these personnel were drawn from TA.

TA were also mobilised to serve during the “May 13” tragedy in 1969 in several parts of the country and they contributed significantly in the restoration of peace and order.

In light of the prevailing threat to security of the nation, and anticipating future needs, plans on the following were approved to be implemented:

| a. |

Reserve Officers Training Units (ROTU) formed in public universities. |

| b. |

More TA infantry battalions were established and the platoons guarding the East-West Highway reorganised. |

| c. |

Regularisation of the mobilised TA units into infantry battalions. |

| d. |

Reorganisation of State LDC into the “500” series Regiment. |

| e. |

A separate command and administrative headquarters for TA was established and this led to the forming of 11th Infantry Division Army Reserve Force in 1982, taking over the command of the TA force. |

“It never fails to touch our hearts that our job, one that we hold so passionately can bring such wonderful memories and create so much more, in the future”.

|

| Captain Tan Hock Hin at Annual Camp training camp in Kuala Kubu Bahru, Selangor, 1964. |

SERVICE RECORDS

| 1 May 1951 – 30 April 1952 |

Junior Civil Liaison Officer, Ferret Force |

| 1 May 1952 – 30 June 1959 |

Home Guard Inspector, Perak State Home Guard |

| 1 July 1959 - 31 January 1961 |

Warrant Officer II, Territorial Army |

| 1 February 1961 |

Commission Officer, Territorial Army |

| 1970s |

Absorbed to Royal Rangers Regiment |

| 11 September 1983 |

Retired from Service |

RECIPIENT OF AWARDS

| 1969 |

Bintang Perkhidmatan Cemerlang Kedah (BCK) |

| 1973 |

Ahli Mangku Negara (AMN) |

PERSONAL VIEWS

Tommy consider himself privileged to have served over eight years (at different times) in Mindef. He particularly recalled with nostalgia his time in the Army Staff Division where he got to perform a part in those critical days in the 70s in the Territorial Army (TA) Directorate. He was a key-member of the project team, inspired by the Director of the Territorial Army then, to review and to restructure the TA into a more relevant and mission-orientate reserve force. He also recalled with much fondness that the team was well-led by the hardworking and dedicated Staff Officer (Grade One) of the Directorate who was from the Royal Signals Regiment. It was certainly a true testimonial to the success of the team that the plans drawn up then were eventually adopted in the reorganisation of the TA into a more credible reserve force.

Tommy would like to draw attention to the Home Guard days, where the Chinese responded to the call to preserving peace and order in 1952-1959. It was amazing to see how the people turned around and played their part as citizens of the country. Record shows 250,000 served as Home Guards and half of this number were made up by those in new villages and Chinese resettlements, one can imagine the huge number involved in service of the nation. They had performed their duty with no payment of salary or allowances. Taking count of the background situation and large numbers involved, it may be said that Home Guards in new villages and Chinese resettlements had played a significant role during the Malayan Emergency.

More importantly, it also shows that the Chinese answered to the clarion call to take up arms in the defence of the nation, which eventually brought Merdeka to our land. A “big” thank you to ALL members of the Home Guard who had rendered service to the nation during the Malayan Emergency.

CONCLUSION

Major Tan Hock Hin (Retired) SN:59596 retired from the Malaysian Army on 11 September 1983 after serving the King and Country with pride and dedication for over 32 years. He is proud to have had the opportunity to serve the country of his adoption, Malaysia. The fact that he was born Chinese and became Malaysian had never bothered him. He is thankful he is still around to give this account of his service to the nation and hope that this article will bring some enlightenment to the readers.

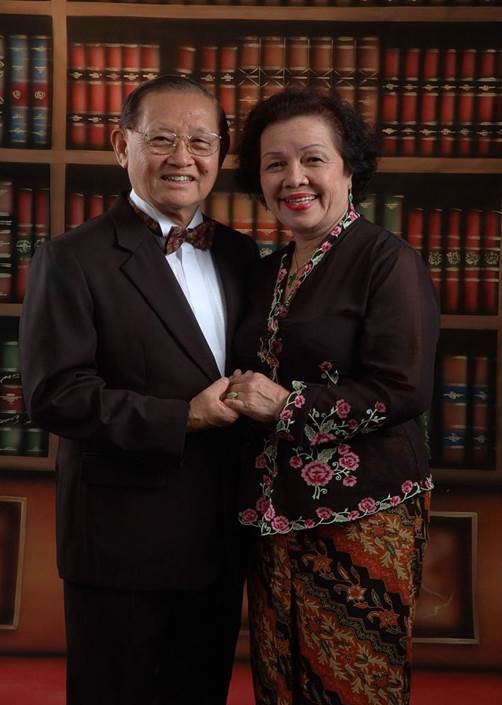

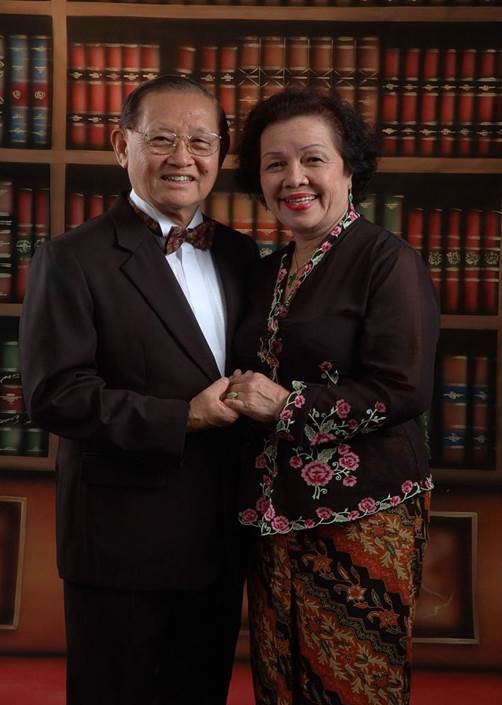

Tommy is married to Lucy Leong Geok Choo and they are blessed with four children, nine grandchildren and seven great grandchildren. They currently reside in Bangsar Baru, Kuala Lumpur.

MACVA is very proud of his achievements and his sacrifices for King and Country. We wish him good spirit and good health in enjoying his well-deserved retirement with his family.

|

| Tommy and Lucy celebrated their Golden Wedding Anniversary in 2005. |

|

| Tommy and Lucy with the family. Photo taken in Melbourne, Australia, 2013. |

Recorded for MACVA Archives.

Maj Wong Kwai Yinn (Rtd)

7 Oct 18